A few months ago, I accidentally bought sneaker proxies. Instead of crying over my mistake, I did what any reasonable person would do: I turned it into science.

You’d think I would have learned something from that experience. You’d be wrong.

This time, I decided to buy ISP proxies; the supposedly fancier kind, somewhere between residential and datacenter IPs. The plan was simple: get a fully rotating pool and add them to my proxy enumeration pipeline for research. The result was, once again, simple but different: I bought the wrong thing.

Despite what the product name proudly advertised ("rotating ISP proxies!"), what I actually got were sticky sessions. These are IPs that cling to you like a desperate ex: great for maintaining a stable session, terrible for enumerating a large IP pool.

So instead of doing the clean, automated enumeration I had planned, I found myself babysitting these stubborn proxies, one request at a time. And since I don’t like wasting bandwidth (or humiliation), I figured I might as well do science with them. Again.

So, what even are these ISP proxies I keep buying by accident

Before we get to the data, let’s take a step back. Clearly, I keep spending money on things I only half understand.

There are a few main species of proxies roaming the internet jungle

- Datacenter proxies – fast, cheap, predictable, and easy to detect.

- Residential proxies – IPs coming from real households, usually routed through other people’s devices or home ISP connections. They look authentic because, well, they kind of are.

- Mobile proxies – similar idea, but with IPs from mobile carriers. Great for pretending to be someone doom-scrolling on a bus.

- ISP proxies – the “premium hybrid” category. In theory, they’re IPs registered under real ISPs, but hosted in datacenters. You get the supposed trust of a residential IP combined with the low latency of a datacenter proxy.

In theory.

It sounds great on paper: the best of both worlds, good reputation, low latency, no messy peer-to-peer networks. The IPs should show up as belonging to a legitimate ISP in WHOIS data, tricking basic detection systems into thinking you’re just another human watching cat videos.

But as we’ll see next, what I actually got looked a lot more like datacenter proxies wearing fake ISP mustaches.

Doing science (again) with the wrong proxies

At this point, it was déjà vu. Different proxies, same regret. But instead of letting my bandwidth quota die in silence, I turned it into another small research project.

The plan was simple: even though the proxies were sticky, I could still enumerate them, just not in the fast, automated way I had planned. So I did it the tedious way, one session at a time.

The process looked something like this:

- Call the provider’s API (

api.provider.com/rotate-proxy-ip) to politely ask for a new IP. - Route a request through that proxy to an API I control that reports information about the IP address that initiated the request, such as its ASN and country.

- Store everything in a JSON file, rinse, repeat, and hope the provider doesn’t start charging extra for persistence.

It wasn’t glamorous, but it worked. Out of 14,000 total requests:

- 13,763 succeeded (no timeouts, no blocks)

- 11,597 distinct IPs were collected

Not bad for a “rotating” proxy service that doesn’t actually rotate.

Even though IP intelligence data such as ASN or geolocation can sometimes be imprecise, you don’t need perfect accuracy to see the pattern. The overall signal was clear enough: what I had in hand didn’t look like real ISP proxies at all.

And the results… well, they spoke for themselves.

So… what are these “ISP” proxies really

After the enumeration, I did what every disappointed researcher does: opened a notebook, ran a few lines of Pandas, and hoped the data would magically make sense. It did, just not in the way I expected.

Here’s the breakdown of the top autonomous systems linked to the proxy IPs I collected:

| ASN organization name | Count of IPs |

|---|---|

| Bunny Communications | 2709 |

| Bunny Communications LLC | 1932 |

| ZTNET Co., LTD | 1651 |

| Arisk Communications Inc. | 998 |

| Wisdom Cloud Internet Technology PTE. LTD | 890 |

| Cogent Communications, LLC | 774 |

| SkyQuantum Internet Service LLC | 738 |

| NeoFiber Communications Inc. | 217 |

| SkyDigital Telecom LTD | 197 |

| Private Customer | 178 |

| Bunny Technology LLC | 175 |

| Tokala Communications Inc. | 162 |

| Global Communication Network Limited | 153 |

| Internet Hostspace Global Inc. | 135 |

| Aulthent | 127 |

If you’ve spent any time around proxy infrastructure, this list probably makes you smile in recognition or wince a little.

These aren’t consumer ISPs. They’re hosting and cloud providers with names that sound like they were generated by an AI trained on “corporate buzzwords + Communications.” You could argue that my definition of ISP proxies may be too strict, but I feel like instead of buying IPs registered to real ISPs but hosted in datacenters, I ended up with IPs registered to datacenters and hosted in… datacenters. Basically, datacenter proxies in an ISP trench coat.

In short, I didn’t get the “best of both worlds” that ISP proxies promise. I got the same old datacenter pool with a stickier personality and a slightly more expensive invoice.

The great ISP proxy illusion (and why it matters)

It’s hard not to feel a little betrayed, though I probably should have seen it coming. The proxy market has a long history of creative marketing.

You know the phrases:

- “Residential-grade!”

- “ISP-verified!”

- “AI-powered rotation!”

It’s the same kind of confident storytelling you sometimes find in the anti-fraud and anti-bot world, where every product is machine learning–driven, zero false positives, and next generation until you actually read the fine print. Different industry, same vocabulary?

ISP proxies are sold as the elegant middle ground between residential and datacenter. In theory, they promise:

- The reputation boost of IPs registered under legitimate ISPs

- The performance of a datacenter connection

- and the illusion that you’re a normal human casually shopping online, not a bot trying to create a few thousand fake accounts for the next “limited-edition” sneaker drop

In practice, some of them fall short. It’s not that all ISP proxies are fake, but you often find IPs registered to companies that sound like ISPs and hosted in regular datacenters. The line between clever sourcing and creative relabeling gets blurry fast.

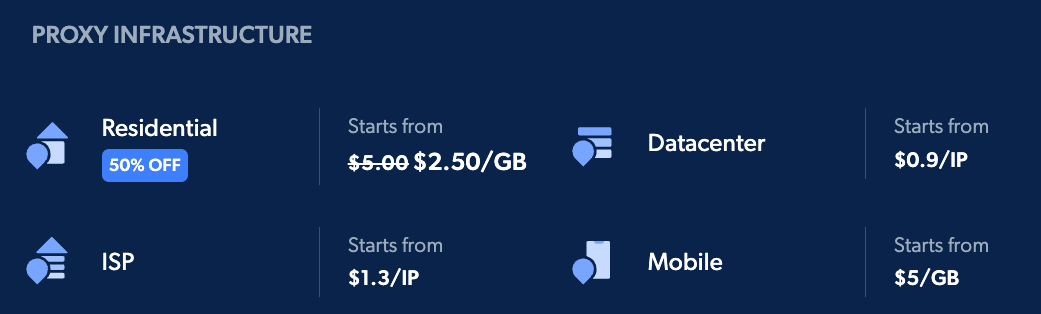

For context, ISP proxies typically cost more than datacenter ones, sometimes much more. As of this writing, Bright Data (which, to be clear, is not the provider studied here) lists prices around $1.3/GB for ISP proxies compared to $0.9/GB for datacenter proxies.

That price gap doesn’t seem huge until you start burning through gigabytes of data. Then you realize your “ISP proxy” is just a datacenter IP with better marketing.

To be fair, not every provider is trying to mislead. Some actually source genuine ISP-allocated ranges. But for every legitimate one, there’s a reseller whose business model is basically: rename, rebrand, resell, repeat.

So yes, once again, I paid for “premium ISP rotation” and got sticky datacenter proxies with a fancier story. Fool me once, shame on me. Fool me twice… at least I got another dataset out of it.

Because this is a security blog, here are the IoCs

At this point, you know how this goes. I bought the wrong thing, ran too many requests, and now I have a dataset that’s too weird not to share.

Since this is technically a security blog, that means one thing: Indicators of Compromise (or in this case, Indicators of Confusion).

I’m releasing two lists derived from the study:

1. Raw proxy IP list

A plain list of all 11,597 distinct proxy IPs observed during the enumeration.

File:

2. /24 ranges with high proxy density

For every /24 network where I saw more than 5 proxy IPs, I assume the entire /24 is part of the provider’s proxy pool.

This heuristic works well for datacenter-style networks, where contiguous IP blocks are often leased in bulk.

File:

Summary:

- total /24s meeting the > 5 IP threshold: 395

- equivalent IPs covered by those ranges: 101,120

These lists are meant for researchers and defenders who want to track large-scale proxy infrastructure.

Bonus: more science (because we were not going to stop there)

We did not stop at proxy IP enumeration. Once the /24 list was ready, we correlated those ranges with the traffic across the customers we protect. The result was not exactly shocking. Many of the IPs from these so-called ISP ranges showed up repeatedly in bot activity, mostly tied to fake account creation and credential stuffing. In other words, exactly what you would expect from a proxy pool marketed as “high-quality ISP traffic.”

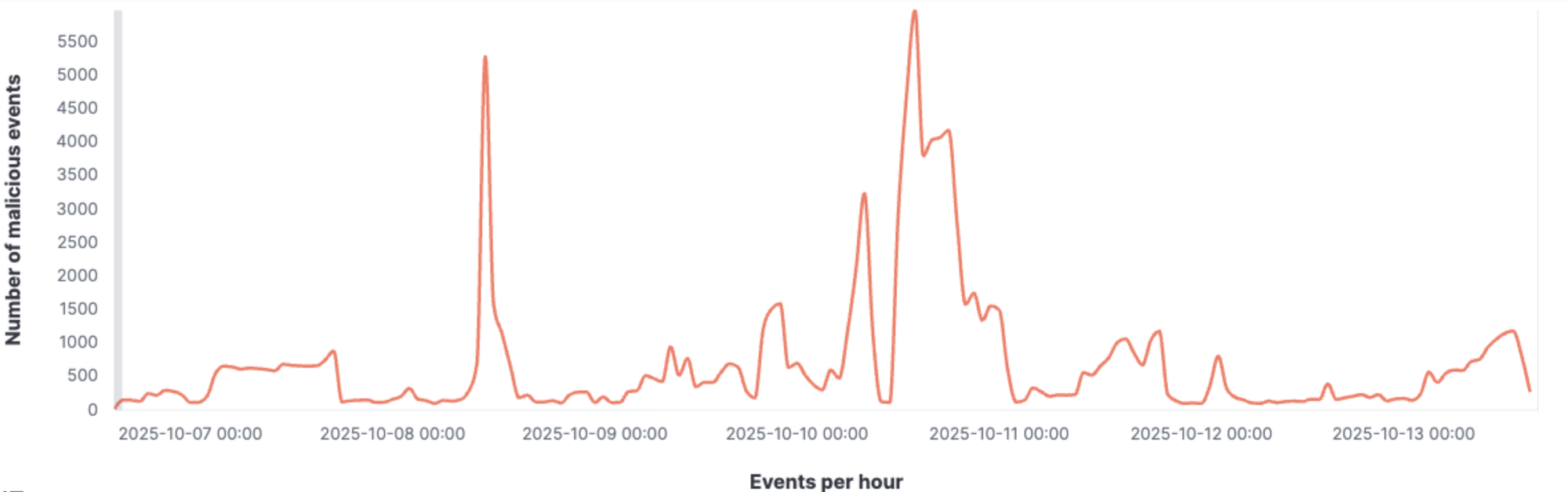

Over a one-week period, we observed more than 116k malicious bot events linked to these proxy ranges (cf screenshot below).

A closer look at those events revealed some predictable patterns

- fake account creation using clearly disposable or custom domains, such as

guoguoguo[.]icuandjoannemalan[.]shop - large-scale account creation using seemingly clean Gmail and Outlook accounts, which helps attackers evade simple domain-based filters

- high-volume credential stuffing against multiple endpoints, often targeting login and password-reset flows

What stood out is that many of these bots had relatively clean client-side fingerprints. They rarely tripped the obvious red flags like navigator.webdriver or blatantly spoofed user agents. In other words, they were not the clumsy scripts of lore. Instead, they looked like professional automation frameworks that pay attention to basic fingerprint hygiene.

That means simple fingerprint checks alone are not enough. Detecting this activity required a layered approach combining:

- behavioral analysis, for example, velocity and session patterns, impossible interaction sequences, or improbable funnel flows

- advanced fingerprint checks, including subtle red pills (timing jitter, canvas/WebGL signal comparisons, font/locale inconsistencies), and correlation of multiple orthogonal signals rather than any single fingerprint bit

- and, of course, proxy and network reputation, which should be obvious by now, given that the entire article started with me accidentally funding a proxy research project

This is the one serious takeaway from the whole story. Even though this post is jokey, the reality is blunt: these proxy networks, whether they are genuine ISP exits or just datacenter pools with better marketing, are used at scale by attackers. That is why detection needs to combine multiple layers of telemetry, from fingerprinting and behavioral analysis to proxy detection and network reputation. When you stitch those layers together, you are far more likely to stop the attacks that really matter, while keeping false positives under control.