If you have been following this series (post 1 and post 2), you know the ritual by now. I buy proxies, they are not exactly what I expected, and instead of quietly moving on with my life, I decide to turn it into… whatever this has become.

When I was a kid, I liked doing unboxings of Pokémon cards. The thrill of opening a pack, hoping for something rare, and inevitably getting duplicates. These days, the packs are proxy plans, the cards are IP addresses, and the disappointment comes with an invoice. Personal growth, or something like that.

This time was no different. I bought a small batch of residential proxies and thought, why not make it content? At this point, I am basically one wrong checkout away from going full influencer.

“Hey everyone, welcome back to the channel. Today, we are opening 1 GB of rotating residential proxies. Will we pull a rare high-quality IP or a common datacenter dud? Stay tuned, because I definitely spent real money on this.”

Jokes aside, there is a reason I keep digging into proxies.

Proxies are one of the foundational pieces of infrastructure that let attackers scale. They let bots lie about their IP address, distribute traffic across thousands of hosts, bypass geoblocking by choosing the “right” country, and borrow reputation from IPs registered under major ISPs. Without large proxy pools, most high-volume attacks would collapse under basic IP-based rate limiting defenses.

And yet the proxy ecosystem is notoriously opaque. Providers claim millions of residential IPs, premium pools, proprietary sourcing, miracle rotation. Behind the marketing, many simply resell the same blocks with different labels. Some “residential” proxies turn out to be ISP-registered ranges hosted in datacenters. Some “premium” pools are just the same low-quality IPs with a nicer landing page.

So I wanted to take another look, not to rate a provider or hand out referral links (I am not there yet), but to better understand how these networks behave at scale and how they surface in real traffic. Which means buying the proxies, routing far too many requests through them, and seeing what the data reveals.

What We Collected, and What Fell Out of the Machine

For this unboxing, I spent about $2.70 on bandwidth, which translated into 1 GB of rotating residential proxies. I know, massive R&D budget. Please respect the process.

The good news is that these were actually rotating proxies. No sticky sessions, no five-minute hostage situations. That made it possible to enumerate the IPs properly, so we routed traffic through the proxies and logged what came out on the other side.

Over the course of the experiment, our endpoint received 780,605 requests coming from these proxies, which mapped to 599,549 distinct IP addresses. With a dataset of that size, the first thing we wanted to understand was whether this pool really looked residential, as advertised, or whether it was a mix of different proxy sourcing strategies.

To do that, we looked at the Autonomous System (AS) associated with each IP. AS information is not perfect, but it gives a useful high-level signal about the nature of an IP address: whether it belongs to a consumer ISP, a business or enterprise range, or a classic datacenter provider.

In other words, it helps answer a simple question:

What type of IPs did we actually get?

Before we go further, here is a quick reminder of the difference:

- Residential proxies use IPs from real consumer devices on home networks. These IPs typically come from well-known ISPs like Comcast, AT&T, or Spectrum, and traffic is mixed with real human activity.

- ISP proxies use IPs registered to major ISPs but hosted in datacenters, not in homes. They look residential in WHOIS data, but behave like proxy infrastructure.

- Datacenter proxies are IPs from cloud or hosting providers. Cheap, fast, and very easy to detect.

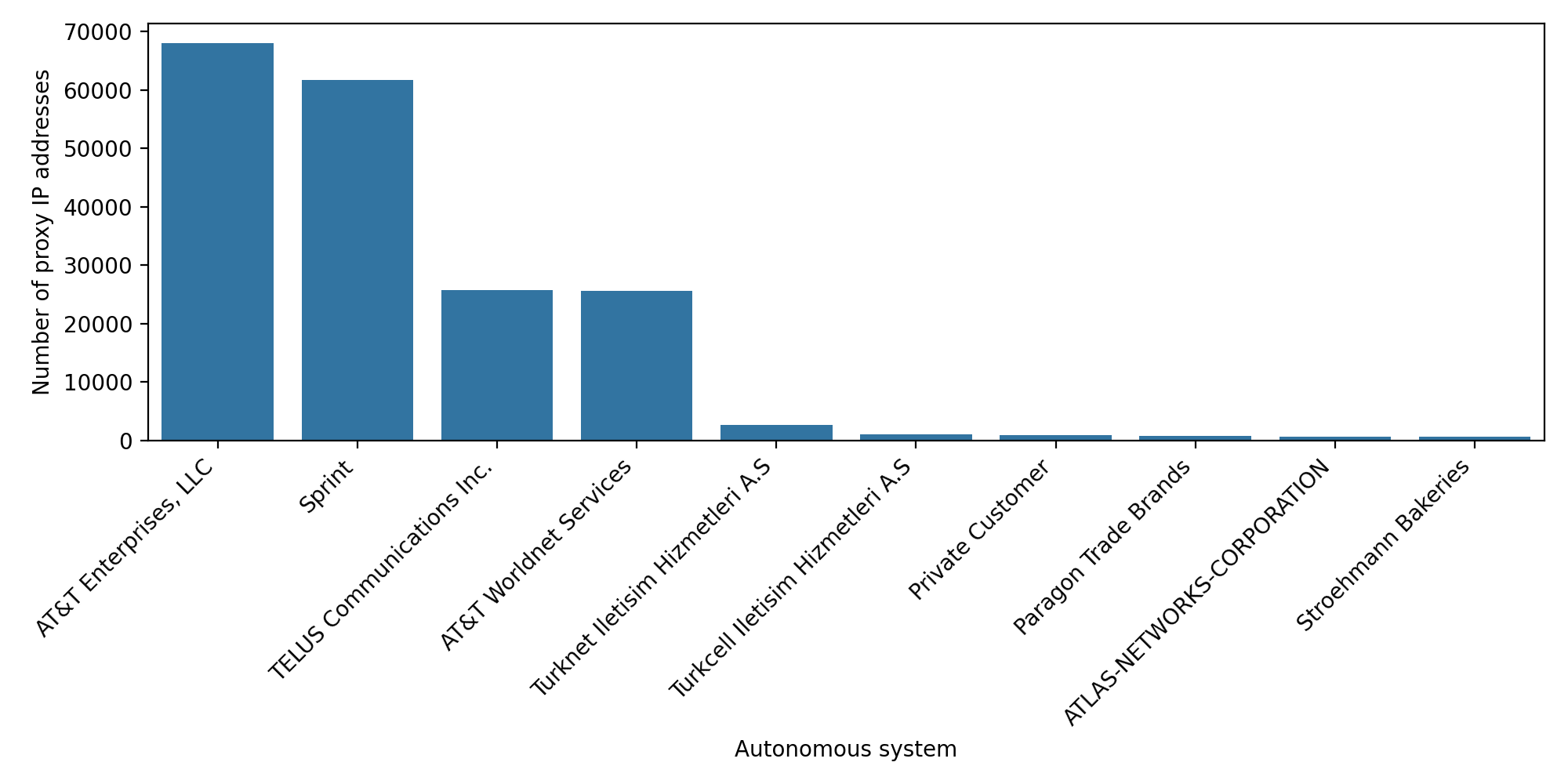

With that in mind, here is what we saw when plotting the top ASNs across all collected IPs:

At first sight, the distribution looks partly aligned with what you would expect from a residential pool. The top entries include names linked to large US ISPs, such as AT&T Enterprise, AT&T WorldNet Services, and Verizon Business. These labels sound “residential adjacent,” which is probably why many providers highlight them.

However, this naming can be misleading.

These ASNs correspond to enterprise and business ISP ranges, which often host network infrastructure in datacenter environments, not consumer homes. So while the proxy provider did deliver IPs registered under big ISPs, it is not clear how many of these are truly residential endpoints versus ISP-style proxy ranges.

There is also a long tail of smaller ASNs, including both consumer ISPs and what look like legitimate residential allocations. So the pool is not obviously low quality, but it is a mix.

At this stage, nothing conclusive. The AS distribution alone cannot tell us whether these are real residential devices or ISP proxies dressed up as residential. The real signal comes from how the IPs cluster in the address space. And that is what we explore next.

Zooming In: /24 Proximity and What It Reveals

Looking at ASNs gives you the first layer of the story. But to get a clearer sense of what kind of proxies we are dealing with, it can help to zoom in further. Not by inspecting individual IPs one by one, but by looking at how closely they sit next to each other in the IPv4 address space.

So we mapped every proxy IP to its /24 range.

For example, 155.26.36.90 becomes 155.26.36.0/24. This groups IPs into buckets of 256 possible addresses and is a useful way to spot patterns that often show up in proxy infrastructure. It is not an exact science, but when ranges show unusually high density, it usually means something interesting is going on.

To make this meaningful, we filtered for /24s where we observed more than 125 distinct IPs, meaning we routed traffic through over half the block within 24 hours. When that happens, it is a strong indication that the provider likely controls the entire range and uses it as proxy inventory.

This yielded 1,421 dense /24 ranges, which is a substantial number for something marketed as residential.

When we plotted the ASNs for those dense /24s, the picture sharpened:

All the miscellaneous residential ASNs fell away. AT&T Enterprise/worldnet, Sprint, as well as Telus communications remained dominant. Everything else turned into background noise.

What this likely indicates

This pattern aligns much more with ISP proxies than with true residential proxies.

In other words:

- The IPs are registered under well-known ISPs like AT&T

- but appear to be hosted in datacenters, not on consumer devices

- and are grouped into contiguous blocks, suggesting dedicated proxy subnets

Real residential IPs do not cluster this neatly. They are distributed across neighborhoods and real homes, mixed with human traffic, and rarely appear in clean, high-density blocks used exclusively for automation. So while the provider marketed these as residential proxies, the structure of the IP space suggests a significant portion behaves like ISP-style proxy ranges.

This becomes even clearer when we look at how these ranges show up in real traffic.

How These Ranges Behave in the Wild

Once we had the list of 1,421 dense /24 ranges, the next question was straightforward: what are these proxies actually used for in real traffic?

So we filtered customer traffic for requests coming from these /24s. The result was immediate. These ranges appeared in hundreds of thousands of bot requests, across websites and mobile apps in very different industries.

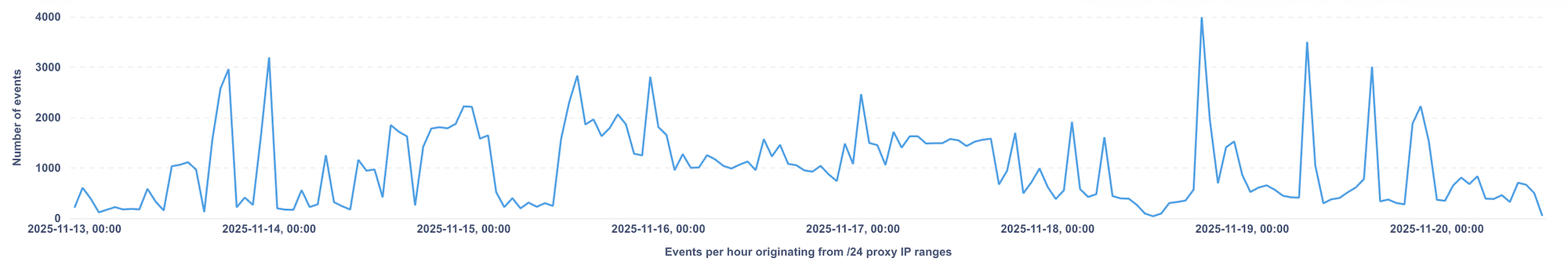

And as you can guess from the graph below, the pattern is not exactly subtle. The spikes are classic signatures of automated activity.

The activity coming from these ranges fits the usual themes: high-volume account creation, opportunistic spam, repetitive credential stuffing, and various forms of platform abuse. Nothing surprising, but it confirms what the /24 proximity analysis hinted at. These blocks behave like dedicated proxy infrastructure, not like scattered residential IPs mixed with normal user traffic.

Why this matters for detection

Blocking proxies outright is rarely safe. Proxy IPs can be shared, repurposed, or mixed with legitimate human traffic, so they should not be treated as a standalone verdict. That said, the situation is different when a pool turns out to be ISP proxies grouped in clean /24 blocks, as we observed here. In that case, it is often safer to block the entire /24, which makes it easier to cut off abusive traffic quickly and reduces the need to chase individual IPs.

In general though, proxy IPs should be treated as a weak but essential signal. Bots rely on proxies to scale. They need large pools to distribute traffic, avoid rate limits, and blend into networks with better reputation. So even if an IP being a proxy does not prove malicious intent, traffic from IPs recently observed as proxies is often an early indicator of coordinated activity.

That is why proxy intelligence works best when combined with multiple layers of telemetry, including behavioral signals, fingerprint inconsistencies, session velocity, routing patterns, and cross-request correlation.

Because This Is a Security Blog, Here Are the IoCs

At this point you already know how these stories end. I buy proxies, run far too many requests through them, and somehow walk away with a dataset that is too oddly specific not to publish. Since this is technically a security blog, that means it is time for the Indicators of Compromise.

Below are the two lists extracted from the study.

1. Proxy IP list

A compressed file containing all 599,549 distinct IP addresses we observed while routing traffic through the proxy pool.

This list is intended for researchers and defenders who want to analyze or cross-reference activity from this provider’s network.

2. Dense /24 ranges

A second file listing all 1,421 /24 blocks where we observed more than 125 distinct IPs in less than 24 hours. This is the heuristic we use to infer that the provider likely controls the entire block and uses it exclusively as proxy infrastructure.

Across all these ranges, that represents 363,776 IPs in total.

If you want to study large-scale proxy behavior or correlate these ranges with your own traffic, these lists provide a clean starting point.

Final Thoughts: What $2.75 Buys You

So that is what $2.75 of “residential” proxies gets you: a large collection of ISP-registered ranges, clean /24 blocks, and a clear window into how this type of proxy infrastructure shows up across industries.

ISP proxies are not necessarily of bad quality. In fact, they are often fast, stable and with a good-enough IP reputation. What matters for defenders is understanding how these networks behave, how densely their IPs cluster, and how consistently they appear in automated activity.

This small experiment gives us another data point about how proxy providers source and structure their pools, and how these IPs surface in real-world traffic. Even a modest dataset can reveal patterns once you start looking at proximity, ASN composition, and how ranges behave under load.

And with that, we can officially close Episode 3 of the ongoing saga:

“Antoine buys the wrong proxies and somehow turns it into an article.”