Modern bot detection rarely deals with obviously fake browsers. Most large-scale automation today runs inside browser instances, with patched fingerprints, realistic behavior, and few visible automation artifacts. This pushes detection systems toward weaker, contextual signals rather than single hard indicators.

Browser extensions are one such signal.

Extensions run in separate execution contexts, but they are not always fully isolated from the page. Many can inject scripts or styles, modify the DOM, expose global objects, or make internal resources accessible to websites. These interactions often leave observable side effects.

At the same time, extensions are commonly used in automation stacks. Scrapers, CAPTCHA solvers, and workflow automation tools frequently rely on extensions to simplify or scale abuse. Even when an extension is not actively used on a given site, its presence can still reveal information about the environment.

Thus, detecting browser extensions provide valuable context when it comes to fraud and bot detection.

In this article, we explain how to detect browser extensions using client-side JavaScript. We start from a real world example and analyze how LinkedIn detects browser extensions. We discuss why this technique works and where its limitations lie. We then contrast it with the stealthier approach used at Castle, which relies on JavaScript and DOM side effects rather than direct resource probing.

Quick introduction to browser extensions

Because extension detection depends on how extensions are built, let’s briefly review what browser extensions are (and what they are not).

Browser extensions are small software components that extend the behavior of the browser.

From an architectural point of view, extensions are composed of multiple parts:

- Background scripts / service workers, which run outside of any page and can maintain state.

- Content scripts, which run in an isolated JavaScript world but have access to the page’s DOM.

- Injected scripts, which some extensions explicitly insert into the page so they execute in the same JavaScript context as the site itself.

- Extension resources, such as HTML, CSS, images, or JavaScript files bundled with the extension.

This split architecture matters because it defines what an extension can change on a page, and what traces it may leave behind.

Although extensions have their own execution contexts, they are designed to interact with web pages. They can inject CSS, add or modify DOM nodes, hook JavaScript APIs, expose globals, or intercept network requests. This interaction surface is what ultimately makes extension detection possible.

In Chromium-based browsers, each extension is identified by a unique extension ID. This ID is stable across installations and users. If two users install the same extension from the Chrome Web Store, the extension ID will be identical for both. This stability is also a key property exploited by detection techniques.

Why extensions cannot be enumerated like plugins

Browser extensions are often conflated with browser plugins, but the two are fundamentally different.

Plugins such as Flash, Java applets, or Silverlight were native components loaded by the browser to handle specific content types. They were historically exposed through the navigator.plugins API, which made them trivial to enumerate from JavaScript. For a long time, this made plugins a strong source of fingerprinting entropy.

That model has largely disappeared.

By 2026, NPAPI plugins are effectively deprecated across all major browsers. Flash is gone, Java applets are no longer supported, and most browsers now return either an empty or standardized navigator.plugins list. As a result, plugin-based detection and fingerprinting is no longer useful in practice.

Extensions replaced plugins as the primary way to extend browser functionality, but browser vendors intentionally avoided repeating the same mistake. There is no equivalent API to enumerate installed extensions.

As a consequence, detecting extensions requires relying on indirect signals rather than explicit enumeration. In practice, this means observing side effects introduced by extensions, such as:

- The presence of extension-served resources.

- DOM mutations or custom elements added to the page.

- JavaScript globals or patched APIs.

- Behavioral changes in how the page executes.

The rest of this article looks at two real-world implementations: a direct probing approach used by LinkedIn, and a stealthier side-effect-based approach used at Castle.

A real-world example: LinkedIn’s extension detection

LinkedIn is a high-value target for scraping and automation. As a result, it deploys multiple client-side fingerprinting and bot detection checks.

A significant portion of this logic appears to be inherited from older open source fingerprinting libraries, including early versions of FingerprintJS. For example, the snippet below checks for the presence of navigator.webdriver, a signal historically associated with Selenium and other automation frameworks:

key: "automationKey",

value: function(e, n) {

if (t.getHasLiedBrowser())

e("undetected, fake browser")

else {

var i = t.getBrowserNameAndVersion().split(" ")[0]

"Chrome" !== i || !0 !== navigator.webdriver

? "Firefox" === i && window.document.documentElement.getAttribute("webdriver")

|| "_Selenium_IDE_Recorder" in window

|| "__webdriver_script_fn" in document

? e("Selenium")

: window.callPhantom || window._phantom

? e("PhantomJS")

: e(n.NOT_AVAILABLE)

: e("Selenium")

}

}This snippet is not directly related to extension detection, but it illustrates the broader goal of the script: identifying automation signals in the browser environment.

LinkedIn’s extension fingerprint list

For browser extension detection, LinkedIn uses a different technique. Their script defines a long static array, named o in the code snippet below, containing objects with two properties:

id: a Chrome extension IDfile: a path to a file inside the extension package

const o = [{

id: "aaaeoelkococjpgngfokhbkkfiiegolp",

file: "assets/index-COXueBxP.js"

}, {

id: "aabfjmnamlihmlicgeoogldnfaaklfon",

file: "images/logo.svg"

}, {

id: "aacbpggdjcblgnmgjgpkpddliddineni",

file: "sidebar.html"

}, {

id: "aafaoenpkipdjipkaanjaacfohggodkf",

file: "injected-script.js"

}, {

id: "aafaommkbfcekikjalmjhimibmoppdpg",

file: "xhrforwarder.js"

}, {

id: "aaglcijplkddfdfkclgbimlpjoljbcio",

file: "x-parser.js"

}, {

id: "aahaojipeodnopcjooapajafgidlefko",

file: "images/nalfe_logo_square_16.png"

}, {

id: "aahogoflghpjkacghggcdcolicipmfpi",

file: "content.styles.css"

}, {

id: "aaidboaeckiboobjhialkmehjganhbgk",

file: "mmt-srcwl-lnhvnslulpnfrvcp/icon128.png"

}, {

id: "aaidebednemijhoeanphidakkjhaanec",

file: "icons/icon16.png"

}, {

id: "aaiicdofoildjkenjdeoenfhdmajchlm",

file: "css/popup.css"

}, {

id: "aainjnbelendpglgndeecjljppfgapoh",

file: "inject.js"

}, {

id: "aajeioaakaifilihejpjaohomikfinhj",

file: "assets/icons/close.svg"

},

// ...

// Linked to Grammarly

{

id: "kbfnbcaeplbcioakkpcpgfkobkghlhen",

file: "src/css/gOS-sandbox.styles.css"

}

]Each entry corresponds to a known extension that LinkedIn wants to detect. The list includes developer tools, automation helpers, scraping-related extensions, and productivity tools like Grammarly.

Worked example: detecting Grammarly

We use Grammarly as a concrete example to illustrate how browser extension detection works. Before looking into the detection logic, it’s worth clarifying how extension IDs and web accessible resources work.

The Grammarly extension is available on the Chrome webstore:

https://chromewebstore.google.com/detail/grammarly-ai-writing-assi/kbfnbcaeplbcioakkpcpgfkobkghlhen

Its extension ID, visible in the URL is kbfnbcaeplbcioakkpcpgfkobkghlhen. This extension ID is the primary identifier used by LinkedIn’s detection logic.

You can also inspect the ID of any installed extension by visiting chrome://extensions, enabling developer mode, and opening the extension’s details page.

Web accessible resources as a detection surface

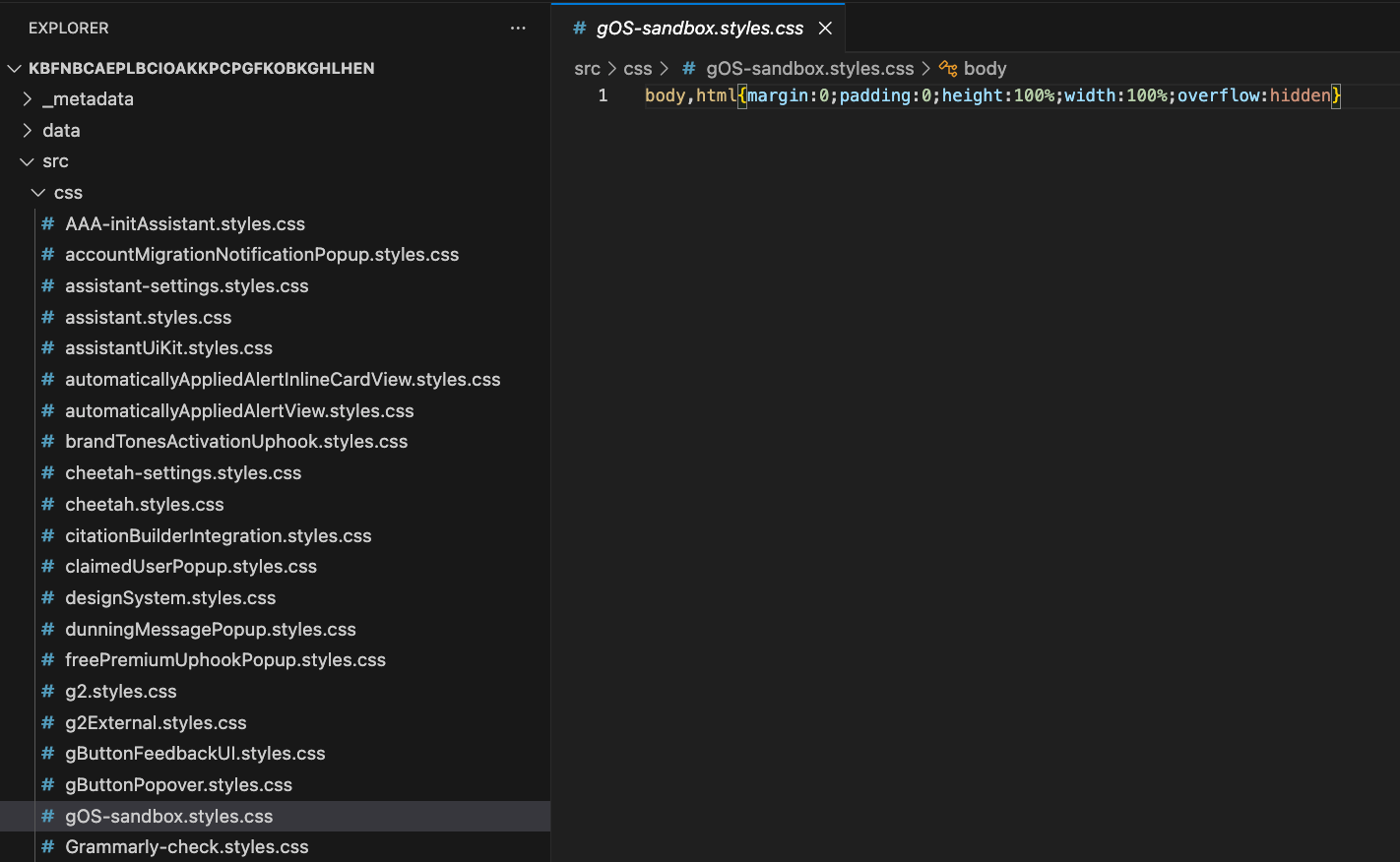

The LinkedIn detection technique relies on web accessible resources. A web accessible resource is a file inside an extension package that the extension explicitly allows websites to request. These resources are declared in the extension’s manifest.json file under the web_accessible_resources field. Web accessible resources exist so extensions can expose assets like images, stylesheets, or HTML pages to the websites they interact with.

If a resource is declared as web accessible, a website can request it using a URL of the form:

chrome-extension://<extension_id>/<path>In the case of Grammarly, LinkedIn probes the following resource:

chrome-extension://kbfnbcaeplbcioakkpcpgfkobkghlhen/src/css/gOS-sandbox.styles.cssIf you inspect the Grammarly extension source code and its manifest.json, you’ll see that this CSS file is explicitly declared as a web accessible resource.

The list of allowed resources is defined in the extension’s manifest:

"name": "Grammarly: AI Writing Assistant and Grammar Checker App",

"short_name": "Superhuman Go (Beta)",

"permissions": [

"scripting",

"sidePanel",

"tabs",

"notifications",

"cookies",

"identity",

"storage"

],

"version": "14.1267.0",

"web_accessible_resources": [

{

"resources": [

"src/fonts/*.woff",

"src/fonts/*.woff2",

"src/images/*.png",

"src/images/*.svg",

"src/images/*.jpg",

"src/images/*.gif",

"src/images/*.webp",

"src/js/*.js",

"src/css/*.css",

"src/icon/toolbar/*.png",

"src/icon/toolbar/superhuman_go/*.png",

"src/icon/app/*.png",

"src/gOS-sandbox.html",

"src/inkwell/index.html",

"src/inkwell/assets/*.js"

],

"matches": [

"http://*/*",

"https://*/*"

]

}

]Because src/css/*.css is declared as web accessible, LinkedIn can attempt to fetch it from any page.

Probing extensions via chrome-extension URLs

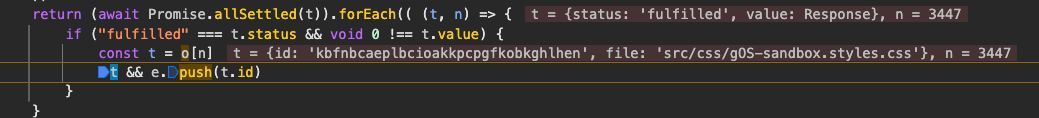

Here is the detection code used by LinkedIn, simplified only for formatting:

function a() {

return "undefined" != typeof window && window && "node" !== window.appEnvironment

}

function s() {

var e, t, n

return (null === (e = window) || void 0 === e || null === (t = e.navigator) || void 0 === t || null === (n = t.userAgent) || void 0 === n ? void 0 : n.indexOf("Chrome")) > -1

}

async function c() {

const e = [],

t = o.map((e => {

let {

id: t,

file: n

} = e

return fetch(`chrome-extension://${t}/${n}`)

}))

return (await Promise.allSettled(t)).forEach(((t, n) => {

if ("fulfilled" === t.status && void 0 !== t.value) {

const t = o[n]

t && e.push(t.id)

}

})),

e

}

async function l(e) {

let t = arguments.length > 1 && void 0 !== arguments[1] ? arguments[1] : {},

n = arguments.length > 2 && void 0 !== arguments[2] ? arguments[2] : {}

if (!a() || !s())

return

const {

useRequestIdleCallback: i = !1,

timeout: r = 2e3,

staggerDetectionMs: l = 0

} = n, d = async () => {

const n = l > 0 ? await async function(e) {

const t = []

for (const {

id: n,

file: i

}

of o) {

try {

await fetch(`chrome-extension://${n}/${i}`) && t.push(n)

} catch (e) {}

e > 0 && await new Promise((t => setTimeout(t, e)))

}

return t

}(l): await c()

Array.isArray(n) && n.length > 0 && e.fireTrackingPayload("AedEvent", {

browserExtensionIds: n,

...t

})

}

i && "function" == typeof window.requestIdleCallback ? window.requestIdleCallback(d, {

timeout: r

}) : await d()

}

const d = "chrome-extension://"

function u() {

return window.document

}At a high level, the logic is straightforward:

- Restrict execution to Chrome or Chromium-based browsers.

- Iterate over the extension fingerprint list.

- Attempt to fetch a known web accessible resource for each extension.

- If the fetch promise resolves, assume the extension is installed.

- Report detected extension IDs to LinkedIn’s tracking backend.

When executing this script in a browser with Grammarly installed, setting a breakpoint at e.push(t.id) confirms that the Grammarly extension ID (kbfnbcaeplbcioakkpcpgfkobkghlhen) is correctly detected.

In the next section, we’ll look at why this approach works, where it breaks down, and what tradeoffs it introduces from both a detection and stealth perspective.

Tradeoffs of chrome-extension resource probing

LinkedIn’s extension detection relies on a simple idea: if a web page can request a resource from chrome-extension://<extension_id>/..., then the corresponding extension is very likely installed.

This works because many popular Chrome extensions expose static assets, such as icons, CSS files, or HTML pages, as web accessible resources. Since extension IDs are stable and globally unique, combining an ID with a known resource path gives LinkedIn a narrow but effective detection surface.

From an implementation standpoint, this approach is attractive. It does not require extension APIs, special permissions, or cooperation from the browser. All it needs is a curated list of extension IDs and predictable resource paths.

However, this technique comes with important downsides.

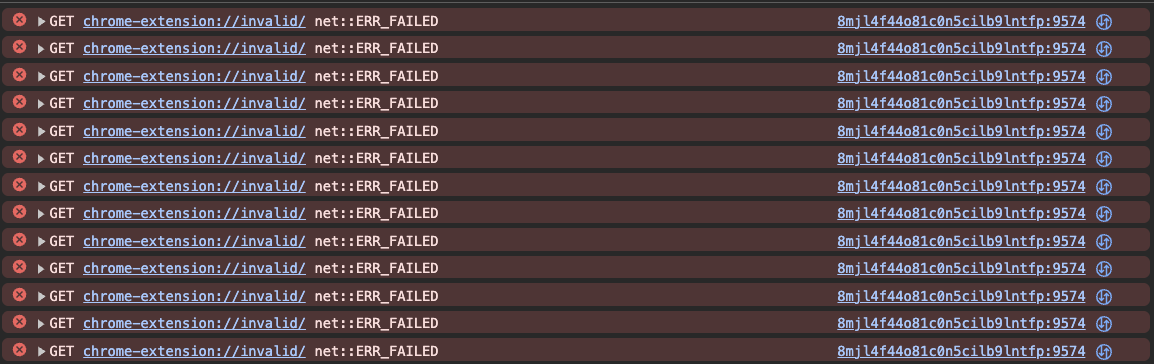

Console noise and observability

When an extension is not installed, requests to chrome-extension:// URLs fail. At scale, this results in a large number of failed requests, which often surface as errors in the browser console.

In practice, running this script produces a visibly noisy console, especially when probing many extensions that are not present.

This noise is observable by anyone inspecting the page, including developers, power users, and browser extensions themselves. More importantly, it makes the technique easier to notice, debug, and potentially counter by attackers who are actively trying to understand or evade detection logic.

Performance and scalability tradeoffs

Probing dozens or hundreds of extensions requires issuing a large number of fetch calls. Even when deferred using requestIdleCallback or staggered over time, this still introduces measurable overhead.

Most websites are not willing to pay this cost in terms of client-side CPU time, network activity, and debugging complexity. The added runtime work and increased observability make this approach difficult to justify unless extension detection is considered strategically important.

Overall, LinkedIn’s method is simple and effective, but noisy and expensive. These tradeoffs help explain why most websites do not attempt browser extension detection at all.

In the next section, we’ll look at a stealthier alternative: how we detect browser extensions at Castle using JavaScript and DOM side effects rather than direct resource probing.

A stealthier approach: extension detection at Castle

At Castle, we also detect the presence of browser extensions, but we take a very different approach from LinkedIn.

Instead of actively probing extension resources using chrome-extension:// URLs, our client-side agent relies on side effects introduced by extensions themselves, observed through JavaScript and the DOM. The goal is to extract useful signal without generating noisy network traffic, console errors, or noticeable performance overhead.

This makes the detection quieter, harder to notice, and easier to run at scale.

Detecting extensions through DOM and JavaScript side effects

Many extensions, intentionally or not, leave observable traces in the page environment as part of their normal operation.

For example, when Grammarly is installed, it injects both DOM attributes and custom elements into the page:

<body data-new-gr-c-s-check-loaded="14.1267.0" data-gr-ext-installed>

It also adds a custom HTML node:

<grammarly-desktop-integrationdata-grammarly-shadow-root="true">

</grammarly-desktop-integration>

Because these elements are present in the page’s DOM, detecting Grammarly becomes straightforward:

function isGrammarlyInstalled() {

return document.querySelector('grammarly-desktop-integration') !== null

}This check does not trigger any network requests, does not generate console errors, and does not rely on extension IDs or internal file paths.

Other extensions expose their presence through JavaScript globals. For example, several crypto-oriented extensions, such as MetaMask, inject an Ethereum provider into the page:

function isMetamaskInstalled() {

return typeof window.ethereum !=='undefined'

}

These side effects are not accidental. Extensions need to interact with the page to function, and that interaction often leaks just enough information to be observable.

Why side-effect-based detection is harder to observe

Compared to chrome-extension:// probing, this method has several practical advantages:

- No failed network requests.

- No console noise.

- No performance spikes caused by large batches of

fetchcalls.

From the browser’s point of view, these checks look like ordinary JavaScript and DOM access. They blend naturally into application logic and are difficult to distinguish from legitimate client-side behavior.

This matters for customers. It allows Castle to extract extension-related signal without degrading user experience or exposing obvious detection artifacts that attackers can observe and adapt to.

Practical limitations

This approach is not universal.

Not all extensions introduce visible DOM or JavaScript side effects. Some only execute on specific domains, some operate entirely in background contexts, and others are deliberately designed to minimize their footprint.

Crafting detection logic is also more manual. Unlike resource probing, you cannot rely solely on an extension ID and a file path. You need a concrete, observable behavior to anchor the detection.

That said, the process can be partially automated. One effective technique is to launch a controlled browser with a target extension installed, load a known page, and diff:

- The DOM before and after installation.

- Global JavaScript objects and properties.

- Patched or wrapped APIs.

This makes it possible to systematically identify stable side effects without relying on brittle heuristics. In practice, this approach trades breadth for stealth. We focus on extensions that matter from a fraud and bot detection perspective, and we detect them in a way that avoids unnecessary noise and performance cost.

Conclusion: extension detection as contextual signal

Browser extension detection sits in an interesting gray area. There is no official API to enumerate installed extensions, and for good reason, but extensions still need to interact with web pages to be useful. That interaction inevitably creates measurable side effects.

LinkedIn’s approach shows that direct probing of chrome-extension:// resources is viable in practice. It can detect a specific set of extensions reliably, but it comes with clear tradeoffs. The technique is noisy, visible, and expensive to run, which limits how broadly it can be deployed without impacting performance or exposing detection logic.

At Castle, we take a different path. By focusing on DOM and JavaScript side effects introduced by extensions, we extract similar signal without generating network noise or polluting the console. This makes the detection harder to observe and cheaper to run at scale, which matters for real-world deployments.

In both cases, extension detection is not a silver bullet. On its own, it is a weak signal. But when combined with other fingerprinting and behavioral indicators, it provides valuable context about the environment behind a request.

As with most modern bot detection techniques, the value does not come from a single check, but from how multiple small signals reinforce each other.